The land of tortured souls

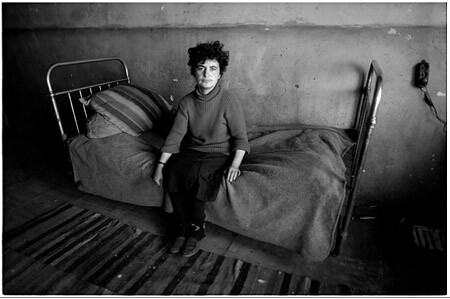

Psychiatric patient at home, Chambarak, Gegharkunik Region, Armenia © Onnik Krikorian / Oneworld Multimedia

Yesterday, the UK's The Sunday Times published a harrowing account by author DBC Pierre of reality as it can be experienced in Armenia. Spending time with the Belgium wing of Médecins Sans Frontières, the writer visited the economically depressed border regions of Armenia to look at the situation of the mentally disabled living in already vulnerable communities. Unfortunately, many of the scenes and stories he describes are true.

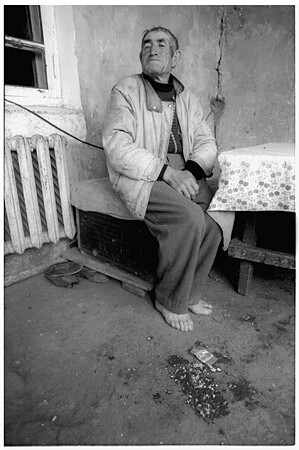

More than a decade after the announcement of ceasefire, much of Armenia still lives in a state of poverty, her infrastructure in decay. Pensions, when they're paid, amount to little over $6 a month, yet fuel costs approach those in the United States. A young republic for the third time in her history, Armenia has no mineral resources to speak of and relies heavily on diaspora Armenians for support. She struggles to find the tools to clear the mess that the 1980s lobbed into her house. In a world intent on the immediacy of conflict, on the savage, newsworthy glamour of unfolding crises, this forgotten place seems a bitter taste of things to come. The taste of a chronic, festering aftermath.

[...]

Not far from the house with the missile sits the border town of Chambarak, comfortably settled into the folds of a high valley. The town is a mixture of rusticity and post-Soviet neglect, an occasional apartment block rising between traditional houses of lava and stone, and smatterings of hay and dung. Some windowsills sport old US Aid tins as flowerpots or buckets, souvenirs of support long gone. A nutty haze of dung smoke hangs over Chambarak, from ubiquitous solid-fuel heaters like large, iron shoe boxes with stovepipes attached. The market building is a vacant shell, attended every day by a crowd of heavily-wrapped men doing nothing and talking about doing nothing. Only one trader is there, selling twigs for broomsticks. 'There used to be nearly 100% employment here,' says a man. 'Now, it's nearly 100% unemployment. Every day there are five funerals, but never a birth.'

[...]

© Psychiatric patient at home, Lchashen, Gegharkunik Region, Armenia © Onnik Krikorian / Oneworld Multimedia

Hamest and her husband are mentally retarded. So are their children. And their life's routine after the door closes behind us is one of unthinkable abuse. Hamest's husband often trades their bread for vodka and drinks with other men in the building, often in that tiny room. He regularly beats Hamest, and there is reason to suspect her daughters suffer sexual abuse at the hands of the men. Hamest's mother is dead, and she has lost all contact with the family she knew when she fled Azerbaijan's capital, Baku, in 1990. She is utterly powerless.

MSF provides Hamest with a grant for electricity, and its psychologist tries to convince her to send her adolescent daughter to a boarding facility, away from the horrors of home. But Hamest is afraid she will lose her daughter as well. I retire from the building with questions. Not least, what are the odds of a mentally handicapped couple finding each other, and going on to raise a handicapped family?

[...]

I learn that when Hamest's husband is out, ranking soldiers from the local base come to the hostel for sex. The kindlier officers might sometimes leave a bag of pasta, or a loaf of bread, for her troubles. The hostel's inhuman feel palls over me. I'm staying in a Soviet apartment in Chambarak, without running water, and with intermittent power. The snow at its entrance has compacted into grey ice, and a puddle of bright blood - hopefully from a freshly killed animal - gilds its shine. Suddenly, it is relative luxury.

[...]

Next day, in nearby Martuni, I meet the region's chief psychiatrist. His office is in a seemingly deserted polyclinic that stands alone in the snow, winds howling through its open concrete foyer. It's bitterly cold inside. No power here either, and the building seems largely empty; only debris and litter are visible through darkened doorways. A nurse ushers us into the office. When Dr Mikayel Kahramanyan arrives, he goes to a cabinet at the back of the room and produces plates of freshly sliced fruit, nuts, chocolate, soft drinks. And brandy. It's 10.30am.

[...]

He agrees there are many institutionalised patients who could be released. But he says the country is still dealing with Soviet structures, and with cultural attitudes. In Armenia, a psychiatrist's report is needed to obtain many types of certificate and licence, including a driver's licence. People won't come forward for treatment, as a psychiatric file would blight them for life. Families shun members with psychoses, and if sufferers aren't committed by their families, they eventually come to the attention of police.[...]

I met many people in the southern Caucasus. Maybe, notwithstanding psychoses brought about by the trauma of war and dislocation, there are no more mental disabilities here than anywhere else. But a great stigma is placed on mental disorder here, and it attaches to anyone within reach of a sufferer. Lesser conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are ignored. And this dynamic forms the heart of Van Baelen's project. He has started on the task of de-stigmatisation.

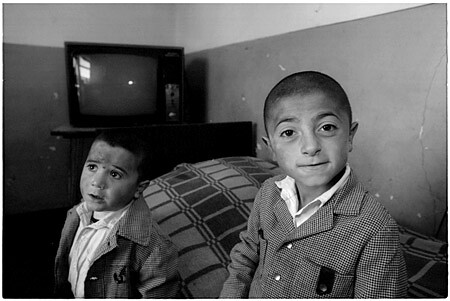

The children of a psychiatric patient at home, Chambarak, Gegharkunik Region, Armenia © Onnik Krikorian / Oneworld Multimedia

The article also details the recent history of Chambarak. If being situated on the border with Azerbaijan wasn't enough thanks to the added problems of landmines, people suffered greatly during the war. As in other border regions of Armenia, such as in north-eastern Tavoush, they still suffer greatly today. I travelled to Chambarak with MSF-Belgium last year as part of my ongoing project on poverty in Armenia which also included a component on mental health. Along with other international organizations, MSF-Belgium is doing something in the border regions of Armenia but not nearly enough simply because finances are lacking.

Now that's somewhere where I would like to see the Diaspora invest its time and resources. For anyone interested, the article also lists details of how you can donate to MSF-Beligium's work in Armenia.Anyway, the full article can be read online here. There are also some related photographs of psychiatric institutions in Armenia in Macromedia Flash format here.

Tag: armenia | poverty | mental health

<< Home